At the GitHub AI Summit, I ran an exercise focused on capacity planning across four teams working on closely related services. Officially, the goal was to ideate how we could better manage our GPU compute capacity. Unofficially, I had a deeper agenda: to reveal just how differently each team saw the system—even though we were all building the same product.

It might sound odd to say I had an ulterior motive, but I’ve seen this pattern everywhere I’ve worked. Even on highly aligned, well-intentioned teams, you’ll often find:

- Engineers struggling to articulate why they made certain decisions

- Every problem labeled as a priority 0

- A culture of short-term tradeoffs leading to long-term burnout

In the AI space, this pattern is even more intense. We’re shipping fast, changing fast, and often skipping the conversations that keep systems coherent. I’ve spent years searching for ways to fix this.

How I Want My Teams to Operate

Over the years, I’ve worked as a PM, designer, frontend dev, and lead engineer. In every role, one thing stands out: every engineer thinks they know exactly what we’re building—until they talk to each other.

That’s when the cracks show. People argue about design decisions with no shared language or framework to move the conversation forward.

That’s why I believe the first two weeks of any project are critical. During this time, a project lead’s most important job is to align the team on what we’re building and how we’ll define success. And that starts with a shared understanding of the system—and the tradeoffs we’re willing to make.

Software Architecture Qualities

There are two tools I use on every project to drive this alignment. The first is Software Architecture Quality Attributes—high-level properties of a system that help teams prioritize and communicate clearly.

Here are a few examples:

- Maintainability – How easily can the system be updated, refactored, or extended?

- Performance – How quickly does it respond under expected and unexpected load?

- Scalability – How well does it handle increasing demands or users?

- Reliability – How often does the system fail, and how gracefully?

- Testability – How easily can the system be tested?

- Deployability – How safely and quickly can we ship changes?

- Security – How vulnerable is the system to misuse or attack?

- Usability (Dev UX) – How easy is it for developers to build on this system?

- Observability – How well can we understand its behavior in production?

- Portability – Can it move across environments or platforms?

These aren’t just checkboxes. They’re tools for tradeoff conversations. And they only matter if they reflect the reality of your system.

“What Even Is My System?”

Using quality attributes gives you a new lens—but you still need to understand what system you’re actually working with. And that’s where things get tricky.

These attributes are context-dependent. “Performance” might mean latency in one system, and memory efficiency in another. What’s critical for one team might be irrelevant to another. That’s why early misalignment is so dangerous.

Engineers bring their biases—often shaped by the scars of systems past. I’ve seen this firsthand: people react to design decisions based on what went wrong in a previous org, even if the current system doesn’t resemble that at all. It’s system PTSD.

To help teams stay grounded in the current system—not the ghosts of systems past—I use tools from design thinking.

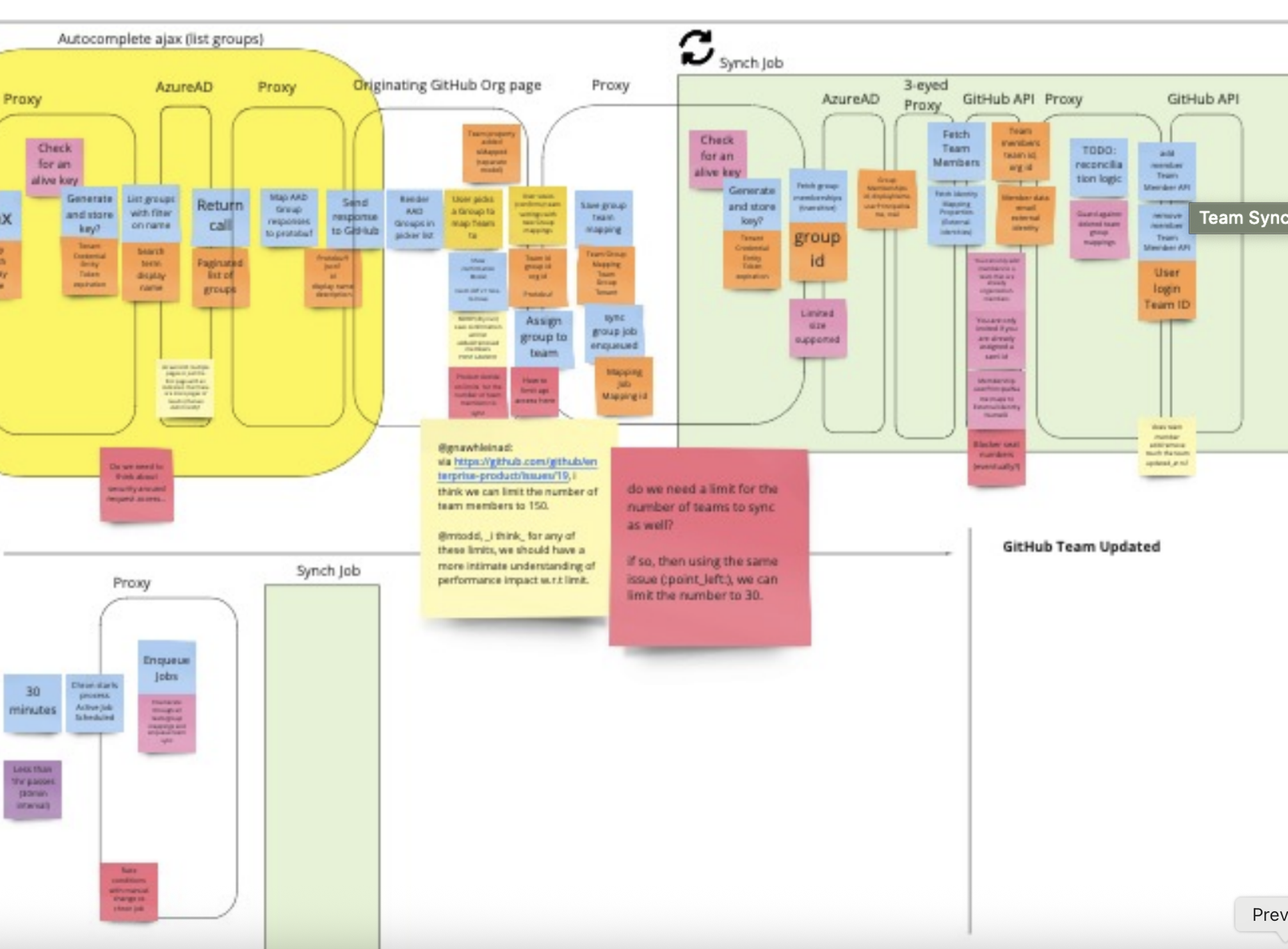

Event Storming

Event Storming, from Domain-Driven Design, is one of the most effective tools I’ve found for quickly building shared understanding.

At its core, it’s a collaborative modeling exercise where engineers, designers, PMs, and stakeholders map out what actually happens in a system—before anyone touches abstractions like classes or services.

You generally want a wide diversity of stakeholders in the room as it will change the conversation and offer new perspectives that will not be there without such diversity.

You can use it to:

- Understand an existing system

- Design a new system

- Plan a refactor

- Integrate a new feature

Basic Event Storming Flow

🟠 1. Start with Domain Events

These are the key moments in your system—things that happen. Examples: “Order Placed”, “User Registered”, “Payment Failed” Write them in past tense and place them left to right as a timeline. 💡 Goal: tell the story of the system in plain language.

🔵 2. Add Commands

These are the actions users or systems take to trigger events. Example: “Place Order” → “Order Placed”

🟣 3. Add Aggregates / Entities

Group related events under domain objects like “User” or “Repository”. This starts to surface ownership boundaries and service seams.

🟡 4. Add Read Models / Queries

What needs to be visible to users or external systems? These show where sync issues, duplication, or design gaps may exist.

🔴 5. Identify Problems and Hotspots

Call out friction: bottlenecks, latency, ambiguity, conflicting interpretations. This is where assumptions surface—and alignment begins.

👉 Here is a simple video explaining how to run your first event storm

Why It Works

- Exposes assumptions – people often think the system behaves differently

- Clarifies language – you start speaking in shared terms

- Builds understanding – you align on what you’re building before the how

💡 Pro tip: Run this early. In the first week of a new project, Event Storming can prevent months of misalignment.

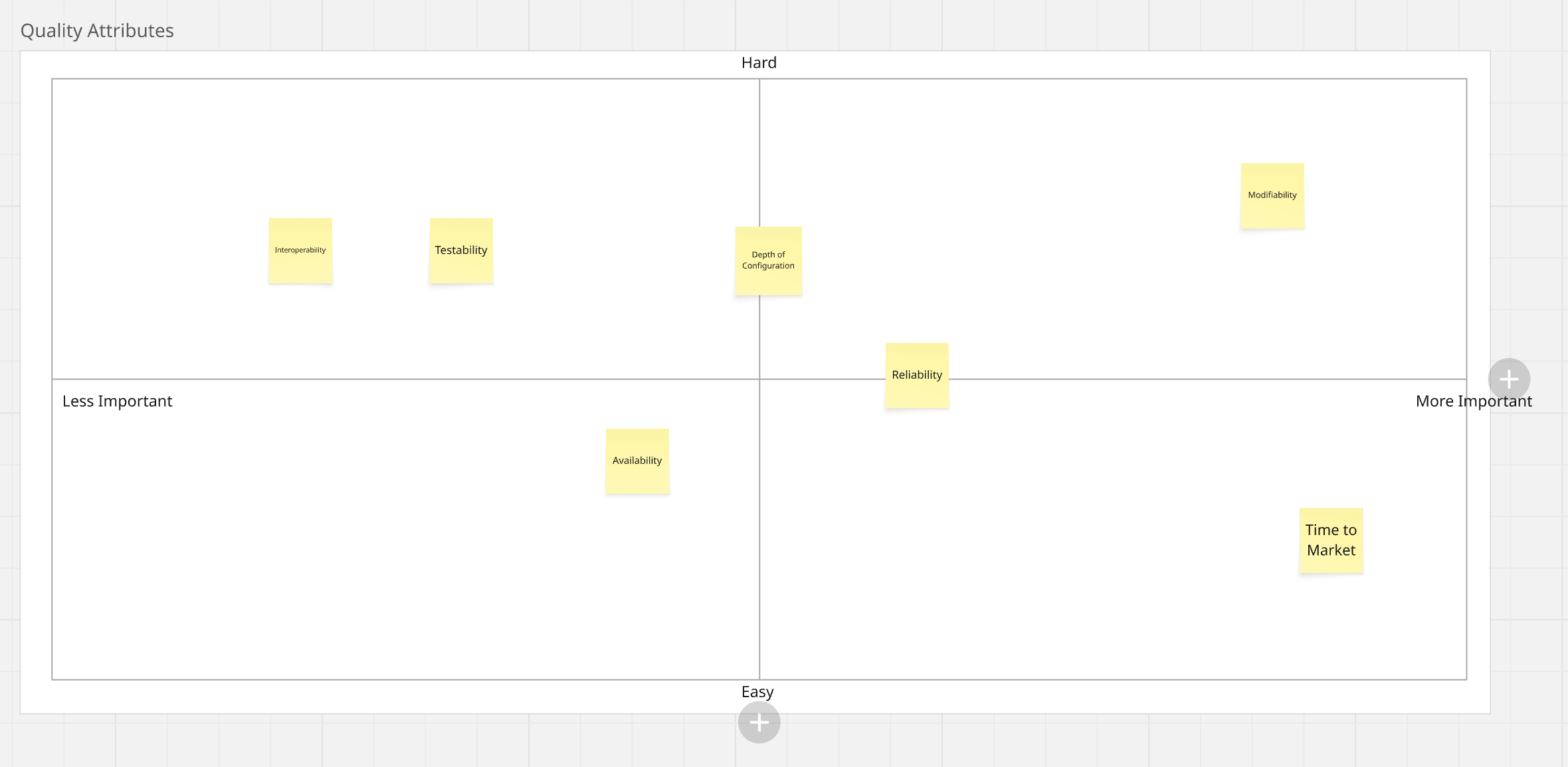

Quality Attribute Ranking

Once the team understands the system and is speaking the same language, I often run a Quality Attribute Ranking exercise.

Setup:

- Write each quality attribute on a sticky note (real or virtual). I start by putting together 7-10 qualities that feel relevant to the system I also include a couple blank post it notes for additional ideas.

- Create an X/Y axis:

- X-axis = Importance (left = low, right = high)

- Y-axis = Difficulty or Current performance (customize based on goals)

- Place the qualities above the x,y axis in no particular order.

Steps:

- Give the team time to reorder attributes silently

- Ask each person to pick 2–3 and explain their reasoning

- Facilitate discussion to resolve disagreements

- Let the team rename, refine, or add new attributes

Once the team agrees on relative importance, evaluate the Y-axis:

- How hard is this to achieve?

- Or: How are we performing today?

This gives you a simple but powerful quadrant map:

- Top-right: Hard and important → Plan for investment

- Bottom-right: Easy and important → Low-hanging fruit

- Top-left: Hard but not valuable → Avoid

- Bottom-left: Easy but not valuable → Ignore or defer

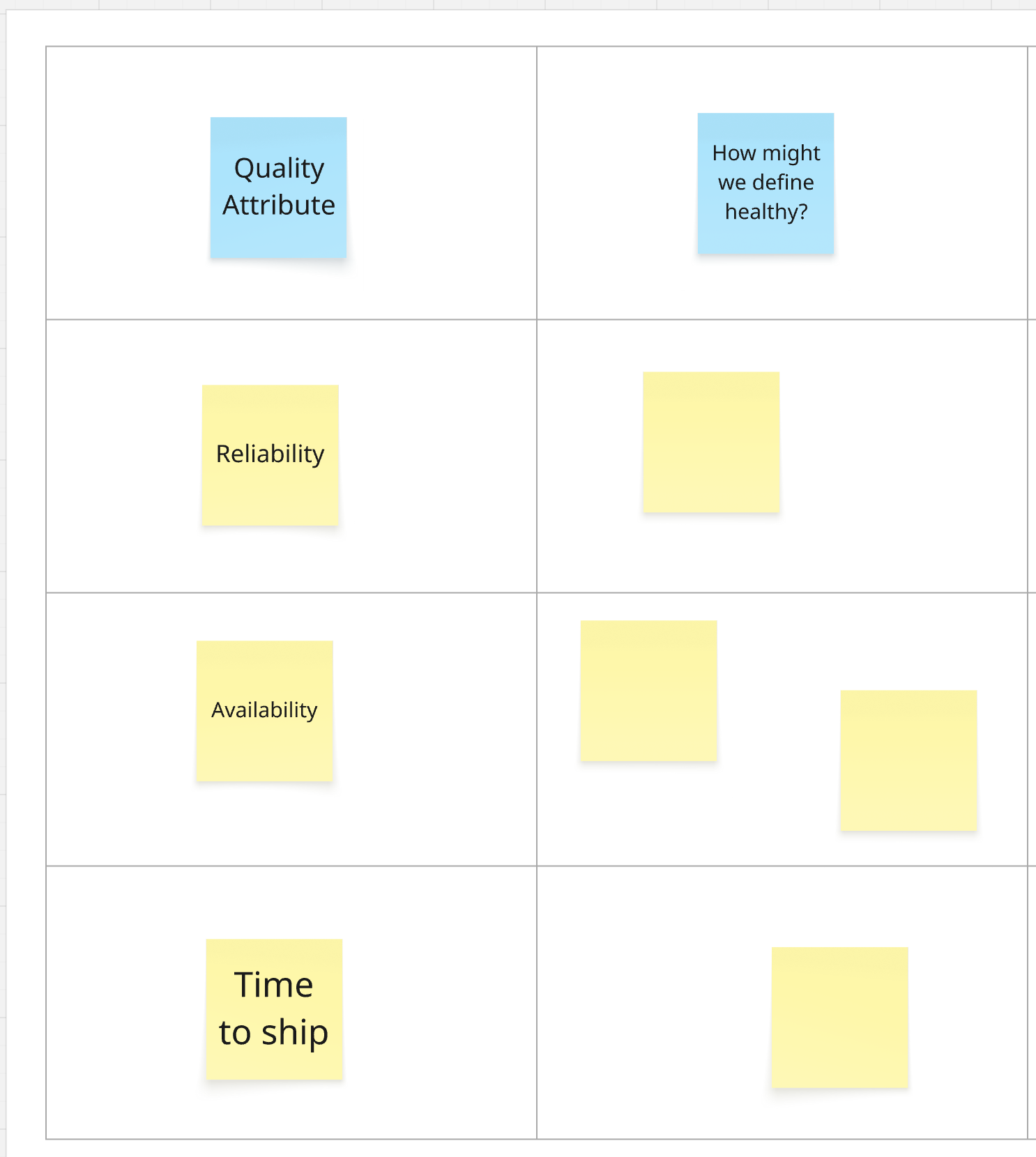

Making Quality Attributes Measurable

Once the team has aligned on which quality attributes matter most, the next step is to define how to measure them.

A quality isn’t useful unless it’s observable, measurable, and enforceable.

Exercise: Defining Health Metrics

- Create a matrix

- Rows: Each prioritized quality attribute

- Columns: Potential health metrics and tools to enforce them

1. Individual brainstorm

- Give each team member 5–10 minutes to write Post-it notes describing what health looks like for each quality.

- Encourage creative or unconventional thinking.

2. Group presentation + dot voting

- Each person presents their ideas

- Group similar or overlapping metrics

- Vote to select 1–2 metrics per quality that best capture the system’s health

3. Reveal tooling options

Once metrics are selected, reveal columns for available tools:

- CI tests

- PR reviews

- Linters / static analysis

- Automated production checks

- Deployment procedures

- Monitoring / alerting

- SLOs / SLIs

- Wildcard (custom mechanisms)

4. Map enforcement mechanisms

- Use sticky notes to explore how each tool might help enforce each metric

- Keep suggestions high-level to encourage fresh ideas

This matrix becomes a living document to translate abstract quality goals into operational practice.

Using Quality Attributes Going Forward

This process doesn’t just drive clarity in the moment—it gives you an artifact to carry forward.

I always document the results of this exercise in an ADR (Architectural Decision Record). From there, I use the ranked quality attributes as:

- A framing tool in future design discussions

- A shared context for evaluating tradeoffs

- A “north star” for system health and alignment

- Tools for testing future changes to ensure they stay in the assigned measurements

In practice, I’ve seen this short-circuit what would be long bike-shedding conversations by providing an agreed-upon, documented ranking of what is important in the system. It also opens the door to quality attribute–driven design.

Creating a Roadmap from Quality Attributes

Once you’ve mapped priorities and defined measurement strategies, the final step is turning that clarity into a roadmap.

Now that you know:

- What matters (X-axis: importance)

- How hard it is (Y-axis: effort or maturity)

- And how to measure it…

You have a practical framework to sequence your investments.

Roadmap Strategy

Start with bottom-right (Easy + Important) These are your low-hanging fruit. I typically assign top 2–3 items for immediate scoping.

Identify top-right (Hard + Important) These are your longer-term bets. Assign 1–2 people to prototype or scope solutions. Timebox discovery work and plan for incremental rollout.

Defer or ignore left side (Less important) Be explicit about what’s not worth investing in right now. This helps reduce scope creep.

Capture Measurement Commitments

You’ve already defined metrics and tools—start acting on them immediately:

- Add failing checks to your CI to raise visibility

- Document the agreed metrics in an ADR or architecture guide

- Automate what you can, even if the baseline is rough

This builds forward motion without requiring perfection.

Final Thought

What does your team think is the most important quality of the system you’re building? If you’re not sure, neither are they.

When developers don’t have a shared understanding of what they’re building, they will each build their own version—guided by past experiences, personal preferences, and invisible assumptions.

Tools like quality attributes and event storming help reveal those assumptions, align mental models, and ground your team in the current system—not a dozen ghosts of systems past.

Great systems don’t come from the smartest individuals. They come from teams who know what they’re building, why it matters, and how to build it together.

Thank you to Len Bass for feedback on this post.